This is one of fifty examples of the last manual machine gun ever adopted by a military power.

This anachronism is called the Bira and hails from faraway Nepal, legendary home of the mythical Ghurkas.

Before we begin: A brief video romp through the workings of the gun from which the Bira was derived.The Gardner, pat.1879 and manufactured by the Hartford, CT newbies, Pratt and Whitney.

And introduced to a lukewarm reception. The US military bought some but they'd already bet on the Gatling and were happy enough with it.

Meanwhile, Pratt and Whitney started letting one of their own engineers play around with the design; sooo... Gardner - feeling jerked-around took his ball and went to Britain.

P&W kept on building them here - their version.

Anyway, watch the vid. Sound track's nothing to shout about.

Well, William Gardner's MG was a big hit in the UK, the reason being: The Gardner was very light-weight considering.

Considering the lightest Gatling, the "Camel Model" was twenty pounds heavier.

Being light, it could be used in the fighting-tops of the ships of the Royal Nav in the ongoing fight against torpedo boats.

If you stuck with the vid long enough to see the workings of it you'll see that Gardner was no dummy.

You can see the Gardner was a seriously elegant piece of work. Joe Nobody (AKA William Gardner) designed this thing and patented it when he was thirty-one years old. Pat. 174130. Anyway, it was the Gardner of the pre-Parkhurst (P&W's engineer) period that provided the inspiration for the Bira.

Back story: 1890's; The Brits, having run up against the Ghurkas previously, were happy to give Nepal lots of weapons as a diplomatic gesture... as long as the Brits could recruit Ghurkas for their own army.

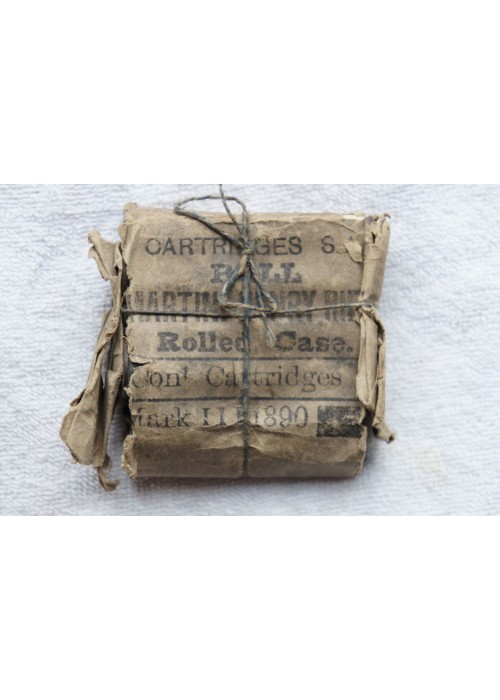

So, Nepal got thousands of Martini-Henry rifles and other stuff including ammo with the blessing of the queen - but no machine-guns.

The British logic was this: If these lovable, child-like Nepalese (If you doubt the paternalistic attitude of the colonizers, read "The White Man's Burden") got hold of just one Nordenfeld or Gardner, those clever monkeys would clone it ad infinitum and Mother England would never sleep secure again.

"Fuck that shit... We've got Tibet for a neighbor which is no fucking picnic!" said Nepal (The translation's rough so I'm paraphrasing).

The Nepalese found a Gardner somewhere - or found the drawings on Google patents - and set about adapting it under the direction of General Gehendra Shamsher Jang Bahadur Rana.

That name will be on the mid-term.

With the Bira, the operating system was the same as that of the Gardner but the feed system was something else again.

See next: Side view (We'll get to the chains in a bit).

First, it's got no vertical, twenty-round, single-stack magazine feeding it like the Gardner has.

It's got a rotating pan - like the Lewis gun but...

whereas the pan of the Lewis held 47 .303 rounds - and the stateside, Gardner's magazine held twenty (The P&W models mounted a double-stack mag of... wait for it... forty!) the Bira's pan carried 120 .577X450, Martini-Henry rounds.

That would be: one-hundred-and-twenty... big-as-your-thumb... bullets.

Up next, The mandala of the Biri gun.

No - wait. That's the ammo pan, seen from below.

Okay, keeping in mind the roundousity of this thing - as well as the bigger-at-one-end trait characteristic of most bullets but especially the .577X450.

They (the cartridges) fit into a circle the same was that 8mm Lebel rounds fit into the half-circle Chauchat mag.

The item pictured measured sixteen inches across and weighed around forty pounds when loaded.

Notice, the perimeter is divided into six chambers.

Likewise notice the teeth along the edge. You can count but there are sixty.

Think; each tooth represents a minute on a clock face. It also represents two rounds; one on top of each other. It's a two-layer cake.

Then, it would logically follow that each of the chambers mentioned earlier, that is 1/6th-of-the-circle, would then contain twenty rounds.

And look at the handy, seemingly ten-round bundles, ready to be untied (A bow knot!) and dumped into one of the aforesaid chambers. Then juggled about until all the pointy ends are aimed at the center of the circle.

Rinse and repeat.

Now, I'm not really sure of the mechanicals of this but; the above depicted mandala is, as stated, a view from the bottom - minus the bottom.

The bottom of the pan wasn't a permanent attachment to the gun but it did remain stationary while the rest of the pan was shoved along by a pawl every two rounds whilst the firing happened.

Pictured next: a right-hand view of the body of the gun without the ammo pan.

Also you'll seen another chain. Notice it. We'll get there. Patience.

We'll likewise deal with that big, brass gear.

First things first.

We now have this double-decker load of ammo being nudged around in a circle.

Eventually each of of these pairs of rounds (one-up, one-down) would come up to the magic door in the stationary bottom of the pan.

It's the hole shaped like a bullet - and exacly as wide as the tooth below it.

Okay, then the bullets fall down as needed, one for each barrel, the pan turns and so on.

As you can see from the two photos of the entire unit, the Birna is mounted like an artillery piece while the Gardner (Lightweight, remember) was mounted either on a tripod or deck mounting.

The benefits that accrue to machine-guns weighing only 110 pounds.

The stately Birna, with a full magazine, would tip the scales at half-a-ton, if you tossed on a bag of dog food.

She is hell-for-stout for certain. Even the screws are huge and, in many cases, only fit that particular hole.

Every one of these guns was built, by hand, one-at-a-time. Consequently, virtually no parts are interchangeable.

One of the other oddities of this gun is that the operating crank turns counter-clockwise as opposed to the opposite direction that the cranks of the Gardner and the Gatling turn.

The good General said that he'd determined that counter-clockwise was a more natural and relaxed motion.

Ooookay.

Remember that big, brass gear that I asked you to notice above.

The Gardner has no such gear. The crank drives the mechanism as fast as it's turned.

On the Bira, the crank turns a small gear which, in turn turns the larger gear - in the opposite direction...

The ratio between the two gears looks to be about one to two-and-a-half.

My first thought was: "Gehendra, you old dog!"

All those precisely mating first-world surfaces with their buttery slidiness were too much for the Bira to measure up to so needed some reduction gearing.

No biggie. We understand. Katmandu isn't Birmingham - it isn't even Hartford.

Good effort.

But then I pondered further.

Recall the political situation mentioned at the start.

Mother England, in appeasing dark-skinned rabble, would not have been giving away any of the good stuff.

This was of course an age when every idea was a new idea and every new idea was a good idea!

Consequently from 1866 on, the British cranked out "Boxer rounds" for the Martini-Henry just like it had been a solid design and so, when a better idea came along - and they were finally convinced to change over, they had lots of the expensive, stupid, transitional cartridges left over.

Regarding the performance of said cartridges...

Maj. E. Gambier Parry, staff officer in the Sudan, regarding the actions at Suakin in 1885:

"The common fault found in them then was that the extractor failed in the performance of its proper functions, and that the rifle was often rendered momentarily useless on account of the inability to extract the cartridge-case after firing without either repeatedly working the lever or drawing the cleaning-rod and forcing the case out by pressure from the muzzle. With regard to the cartridge itself, fault was found with its construction; but we were informed that the cartridge was only experimental, and would be replaced by a better one later on. However that may be, the clumsy built-up and bottle-shaped cartridge has been in use in the army ever since, and no other cartridge has ever been supplied; and more than this, a price is given per thousand for the empty cases returned into store. Thus the cartridges are refilled and the error continued ad infinitum.

...but I see no reason why all these built-up cartridges should not be got rid of at target practice, and reloaded as often as you like, provided they are not issued to men going on active service. It not unfrequently happened that the base of the cartridge was torn right off by the jaws of the extractor, when the rifle was at once rendered utterly useless. The sand and the temperature may have had a certain amount to do with the jamming, but the fault lay principally in the extractor of the rifle and the form of the cartridge. The extractor ought certainly to be improved upon if this rifle is to continue the arm of the services; and a drawn copper cartridge-case, unlubricated, should take the place of the present one. Many men have lost their lives through these two things in our late wars; and though years ago reports, as I say, were made by those best able to judge on the defects of the weapon and the cartridge, no notice was ever taken, and thus through a love of cheese-paring economy, and a penny wise and pound foolish policy, valuable lives have been sacrificed."

Not just for target practice.

That brain-wave of 1866 the was also the perfect thing to spice up those crates of rifles etc. that the Nepalese were receiving.

It's a safe bet that most, if not all, the .577x450 ammo the Brits graciously donated was this.

Now, imagine that your machine gun would be expected to be fed with the potent round shown next, pictured along with partial remnants of another.

All of a sudden, the idea of slowing down the action so these fragile constructions can make their way through the action of the gun without breaking apart, makes a lot of sense.

Another benefit is that the action would be smoothed out and less jerky - I assume.

Now, the chains; remember them?

They form a sort of sling for the two barrels so that, in the event they experienced a failure-to-extract malfunction, the barrels could be handled safely if they were hot.

The barrels were mounted in a cradle and secured by a pin (with a chain - the other chain).

Stoppage = Pull the pin, drop the barrels, poke out the offending cartridge and get back to business.

The chambers were integral with the barrels so nothing got out of alignment.

Maybe this thing was like the early M-16 and just needed to have a rod poked down its throat every now and again.

The similarities end there. The early 16 was a poorly-tested abomination while the Bira was (In my opinion) a nice solution to an odd problem: Buttloads of ammunition - but all of it crap.

The Nepalese never fired them at anyone. They built fifty of them. I assume, tested them and put them away.

But,

Good news, everyone!

They all seemed to have ended up here and - they're a purchasable item!

Check it:

$27,500 get's thing one in your cart.

Of course... it's used. And probably dirty.

And Oh-My-Fucking-God, look what it would cost to feed!

This sucks.

Being that these are an automatic (kind of) weapon, therefore it's just what the framers wanted for us...

And I want one.

There must be a better way!

Just settle down.

This one doesn't seem to be in production yet but it's in .22 mag.

Here though... a genuine knock-off of Pratt & Whitney's knock-off of the Gardner, chambered, like the P&W guns, in .45x70 govt.

$29,950.

So folks, this is the ultimate stealth machine gun.

It's classed the same as a semi-auto rifle.

Moron Labia, Obama!

Awesome.

jordans

ReplyDeletenmd

balenciaga shoes

golden goose outlet

off white shoes

bape hoodie

yeezy shoes

balenciaga

balenciaga speed

nike x off white

i loved this m0j38t0r00 replica ysl replica bags online pakistan replica bags online shopping india hermes replica d0r76d9c22 hermesreplica bags neverfull replica bags nyc replica gucci m5b73m7w49 replica bags ru

ReplyDeletezaaogiu92c3

ReplyDeletegolden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

supreme outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet