a well-respected

engineer and a proven designer of multiple, railroad structures - who

landed his dream job. And this cushy gig just happened to be the

construction of the longest railroad bridge in the world.

Some last minute adjustments had to be made during construction

but - he pulled it off.

He so impressed the Queen that he's knighted.

Pretty sweet, right?

Well then: Just suppose that, at some painfully close interval, and

further, just because we know the universe can be cruelly ironic on

occasion, let's say: His downfall occurred during a season of peak

impact, ie the holidays, and that it impacted his own family.

It happens: The bridge fell down. With a loaded passenger train

crossing - carrying our hero's son-in-law.

That'd be pretty bleak - even for '70's movie.

Welcome to the world of Sir Thomas. Acclaimed designer of the

Tay Bridge and father-in-law to one of the seventy-five or so folks

aboard. Only sixty were ever accounted for. All died.

Sir Thomas died less than a year later.

Short version: A gale-force wind was blowing up the Firth of Tay

(firth = tidal estuary) off the North Sea just as a passenger train

was crossing and the elevated section of the bridge, the so-called

"high girders", blew down due to the action of the wind on the

rail-cars.

So, a monumental fuck-up occurred which put poor old Thomas on the carpet.

What was revealed was a mix of inadequate design, poor manufacturing

standards and a plan that changed radically when it was discovered

that the bedrock they were so confident was close to the river bottom,

turned out to be consolidated gravel.

The root of every part of the problem lay in the nature of the

material used - cast iron.

Cast iron (Actually just an extremely high-carbon steel) is great

stuff. it flows nicely into molds and has awesome strength... in

compression. Keeping it positive; it also has excellent resistance to

deformation under heat and excellent dimensional stability.

It doesn't suck for bridges either, at least sometimes. Others such as

the Dee Bridge, which collapsed thirty years earlier should have clued

them up that they ought to be paying attention.

What put Britons agog over this wonder material was the Crystal

Palace. Built for the Great Exhibition of 1851, it was nothing but a

huge greenhouse (990,000 square feet. Think twenty Home Depots) made

from nothing but cast-iron and plate-glass. Good looking as well.

You can't blame folks for thinking "Holy shit! if we can build that,

we could build a space ship out of this stuff!"

Baby steps. Besides, they weren't completely pulling out of their ass.

in 1781 the impressively named "Iron Bridge" opened.

It was never intended for rail traffic and, in the modern world, if you want to cross, you

have to walk over it - but you can do that - today.

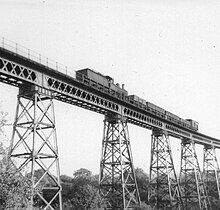

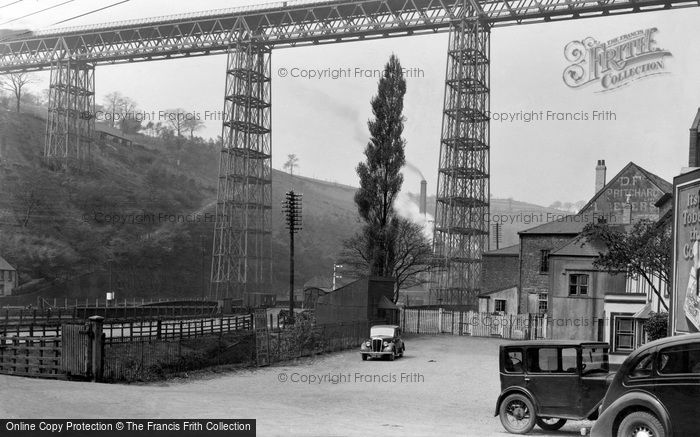

Then there was the Dowery Dell Viaduct that operated from 1878 to 1964

which was only dismantled because the rail line shut down.

The Crumlin Viaduct opened in 1857 and the last passenger train

crossed it in 1964. A passenger train.

The Belah Viaduct was first crossed by a locomotive in the fall of 1860 and continued in regular use until1963.

I think one conclusion we can draw is: Cast-iron doesn't totally suck when it comes to bridges.

A further conclusion can be reached when, after reading the following, that Thomas Bouch was hardly a dummy when it came to bridges.

"The Crumlin Viaduct, of which a description has been given in our previous work, was

doubtless the model after which the Belah was designed, but the

Engineer, Mr Thomas Bouch, of Edinburgh, did not follow Mr Kennard’s

example, except in the general scheme of skeleton trussed piers,

composed of cast and wrought iron, and a superstructure composed of

lattice girders crossed with timber."

Okay then. what the hell happened at the Firth of Tay?

Okay, we've already mentioned the unpleasant fact that all their best-laid plans were thrown into turmoil by the revelation that - what they'd supposed was bedrock was actually consolidated gravel.

landed his dream job. And this cushy gig just happened to be the

construction of the longest railroad bridge in the world.

Some last minute adjustments had to be made during construction

but - he pulled it off.

He so impressed the Queen that he's knighted.

Pretty sweet, right?

Well then: Just suppose that, at some painfully close interval, and

further, just because we know the universe can be cruelly ironic on

occasion, let's say: His downfall occurred during a season of peak

impact, ie the holidays, and that it impacted his own family.

It happens: The bridge fell down. With a loaded passenger train

crossing - carrying our hero's son-in-law.

That'd be pretty bleak - even for '70's movie.

|

Tay Bridge and father-in-law to one of the seventy-five or so folks

aboard. Only sixty were ever accounted for. All died.

Sir Thomas died less than a year later.

Short version: A gale-force wind was blowing up the Firth of Tay

(firth = tidal estuary) off the North Sea just as a passenger train

was crossing and the elevated section of the bridge, the so-called

"high girders", blew down due to the action of the wind on the

rail-cars.

So, a monumental fuck-up occurred which put poor old Thomas on the carpet.

What was revealed was a mix of inadequate design, poor manufacturing

standards and a plan that changed radically when it was discovered

that the bedrock they were so confident was close to the river bottom,

turned out to be consolidated gravel.

The root of every part of the problem lay in the nature of the

material used - cast iron.

Cast iron (Actually just an extremely high-carbon steel) is great

stuff. it flows nicely into molds and has awesome strength... in

compression. Keeping it positive; it also has excellent resistance to

deformation under heat and excellent dimensional stability.

It doesn't suck for bridges either, at least sometimes. Others such as

the Dee Bridge, which collapsed thirty years earlier should have clued

them up that they ought to be paying attention.

What put Britons agog over this wonder material was the Crystal

Palace. Built for the Great Exhibition of 1851, it was nothing but a

huge greenhouse (990,000 square feet. Think twenty Home Depots) made

from nothing but cast-iron and plate-glass. Good looking as well.

You can't blame folks for thinking "Holy shit! if we can build that,

we could build a space ship out of this stuff!"

Baby steps. Besides, they weren't completely pulling out of their ass.

in 1781 the impressively named "Iron Bridge" opened.

| They held a naming contest and this entry squeaked by just ahead of "Bridgy McBridge Butt". |

It was never intended for rail traffic and, in the modern world, if you want to cross, you

have to walk over it - but you can do that - today.

Then there was the Dowery Dell Viaduct that operated from 1878 to 1964

which was only dismantled because the rail line shut down.

The Crumlin Viaduct opened in 1857 and the last passenger train

crossed it in 1964. A passenger train.

The Belah Viaduct was first crossed by a locomotive in the fall of 1860 and continued in regular use until1963.

I think one conclusion we can draw is: Cast-iron doesn't totally suck when it comes to bridges.

A further conclusion can be reached when, after reading the following, that Thomas Bouch was hardly a dummy when it came to bridges.

"The Crumlin Viaduct, of which a description has been given in our previous work, was

doubtless the model after which the Belah was designed, but the

Engineer, Mr Thomas Bouch, of Edinburgh, did not follow Mr Kennard’s

example, except in the general scheme of skeleton trussed piers,

composed of cast and wrought iron, and a superstructure composed of

lattice girders crossed with timber."

Okay then. what the hell happened at the Firth of Tay?

Okay, we've already mentioned the unpleasant fact that all their best-laid plans were thrown into turmoil by the revelation that - what they'd supposed was bedrock was actually consolidated gravel.

But... in for a penny, in for a pound. So much had been committed already that the design was "adjusted".

The original, structure begun in 1871, was to be a bridge supported by brick piers resting on bedrock. Safe as houses, sounds like. If that had been the case, it would likely still be in service today - in its original configuration.

Initial borings had shown the bedrock to be relatively close to the bed of the the river. Accordingly, at either end of the bridge, the bridge were deck trusses, the tops of which were level with the pier tops, with the single track railway running on top. Pretty standard and nice and solid.

However, in the center section of the bridge (the so-called "high girders"), the arrangement was reversed. Instead of having a solid, latticework frame under the rail bed like the rest of the bridge, the high girders were trusses on either side of the track to allow clearance for sailing ships. No flies on any of this - so far.

Before we discuss this delightful graphic it should be noted that the modifications made to the original plan primarily consisted of cutting down on the load carried per pier.

Sir Tom was no dummy but he wanted to keep his gig. Time for compromise. More and narrower piers upon which the roadbed rested as well as lessening of the lateral supports between the cast iron columns and, hey presto, Tom's a peer of the realm.

More fun graphics:

The black diagonals in the first gif represent the wrought iron cross bracing, which was lessened and lightened for the new and improved version of the bridge.

Thing is: wrought iron, given its fibrous structure, has awesome strength in tension. It's not at fault in the least - aside from the fact that there were rather less of the brace/lug connections, as pictured above - breaking - that there ought to have been so ...

Cast iron, as stated kicks, ass in compression but isn't worth a shit in tension.

Over the course of investigation it was discovered that the founders of the columns had, shall we say, cut some corners.

First off: that nice connection that we've been watching fail for lo-these-many-seconds was made by either a pin or bolt - and of substantial size I should think. The holes in the wrought iron laterals were likely bored with whatever precision was usual for the time, being that we still have such bridges today.

In the lug portion of the connection things were iffier.

Being that these columns - eighty-five feet high - were braced by these diagonal brace connections, it would seem that this would bear some special attention. Didn't happen.

Now, not only are we getting by with narrower piers and fewer columns, the manufacturing standards I mentioned at the outset were also in the equation.

Pictured above: An illustration showing the concept of draft. Draft is the process whereby you can extricate the pattern from the mold after ramming,without tearing chunks out of your molding sand.. Making that process clean saves much time and labor in later clean-up. "A clean pattern-draw" is what it's called by trade and industry professionals.

Just because that's the picture I found - and the principles are identical - pretend that what's pictured is the profile of a hole.

Thing is: Every one of those oh-so-critical connections twixt cast columns and wrought iron diagonal braces (If I may belabor the point; with fewer of both which meant a more highly stressed joint than originally planned.) was assembled with the flange holes as pictured (Reverse it). As in: Un-machined, tapered and cleaned-up just enough for the connecting bolt to go through.

Good enough is good enough! It's Miller Time.

At the inquiry it became plain that no one had given a thought to taking the extra time and expense to bore these holes out for a tighter fit. The boss of the foundry said that if no one asked for it special - and no one had - it wasn't their problem.

The other issue was, as mentioned in the title "Beaumont Egg". As near as anyone can gather, this waa 'cockneyisation' of "beau montage". French speakers chime in. It was a term used by French joiners to describe filling the cracks in your new joinery project before it went to its happy new owner. Sort of like: "They'll never see that from a trotting horse" - a My Dad-ism.

Bottom line: It's Bondo. And there is nothing wrong with that except... it was used on structural members.

I was looking for more info on the beaumont egg stuff and found a forum for those arcane anoraks who restore Victorian era machinery, stationary power tools and the like. The warning was given to readership not go too crazy with your brand-new, three-thousand pound bandsaw and put paint stripper on all the cast parts. If in doing so, you uncover some beaumont egg you may just accidentally melt it out of the hole in the casting you never knew was patched thus. And, depending, the stripper may have contaminated the cavity so...

So what was this stuff? It could have been iron-fillings, alum and violin rosin. Or it could have been lead shot pounded into blowholes and sand inclusions. One later account it that steel shot - as used in shot-blasting - is mixed with Portland cement and the whole is pounded firm with a pneumatic hammer. What ever comes to hand that will keep the paint level with the rest of the surface and let you get this damned thing out the door.

It seems that the inciting incident was, as illustrated in the gif, a derailment at the beginning of the high-girders. Followed by the passenger cars falling against the leeward trusses due to the gale-force winds happening in the moment (Another embarrassing query during the inquiry concerned whether Boucher had taken wind loads into account in his design - he hadn't. It simply hadn't come up) and then there follow a wonderful cascade of failures that put him in the doghouse and occasioned the construction of a new bridge.

The piers are still there, right next to the new bridge.

But c'mon now. Turn that frown upside down. There was a survivor - the locomotive later known as "The Diver" (I made a rhyme AND I didn't include 'MacGyver'. You're welcome).

After spending some time in the mud, this valuable, capital asset of the British Northern Railway, was dragged out and put back in service. By the way, pictured below is not the Diver, merely a representative of the type, the NBR 224 series.

After being dragged out of the muck on the third attempt, in 1880, she was refurbished and continued in service until 1925

Gonna close as this is depressing.

I have a copy of a book written in 1956 that is currently available on Amazon

ReplyDeleteThe High Girders: The Story of the Tay Bridge Disaster

https://www.amazon.co.uk/High-Girders-Story-Bridge-Disaster/dp/0140045902

zx flux

ReplyDeleteair jordans

golden goose outlet

nike epic react

nike cortez men

off white shoes

curry 5 shoes

christian louboutin shoes

balenciaga

golden goose sneakers

kuuaicii791

ReplyDeletegolden goose outlet

supreme outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet